Breadcrumb

Student gastronomes plan recipe for Madagascar’s future

As the world celebrates the Africa Day of School Feeding, school children in southern Madagascar are learning how to cook nutritious meals which ultimately may contribute to the longer-term development of vulnerable communities.

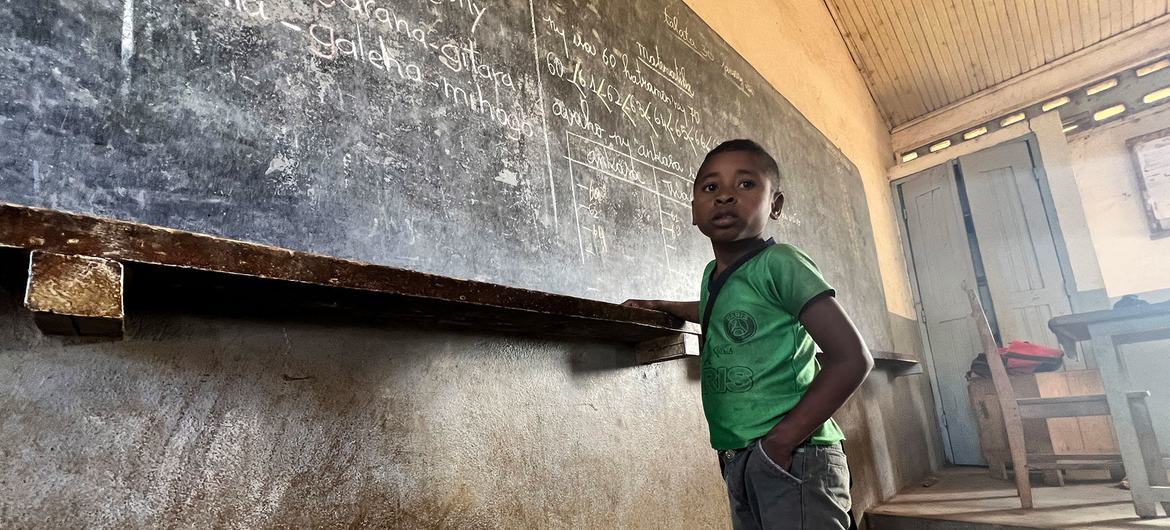

At Beabo Primary School in Ambovombe in the south of Madagascar, teams of students are in competition to cook the tastiest and most nutritional meal using locally available products which hopefully will encourage their parents and others to change to healthier diets.

Fifteen-year-old Marie-Eliane is one of six junior chefs who have produced an impressive three-course menu bursting with varied flavours.

Poached green papaya with boiled organic eggs topped with watercress in an orange and passion fruit dressing is served up as a starter. For the main dish, a manioc and fish stew with nutritionally-rich moringa and anamalaho leaves and for dessert, a fruit salad of cactus prickly pear, watermelon, orange juice and banana.

Her team is cooking off against six others vying to be named the best in a culinary competition known as Tsikonina, a type of Malagasy tea-party game for children.

“I have enjoyed thinking of new recipes especially when they taste so good,” she said. “I hope to persuade my parents to eat this type of food.”

The idea behind Tsikonina, which was set up by the UN in Madagascar, is to educate young people about the preparation of nutritious food and provide them and their families with the knowledge about how to eat healthily keeping within a tight budget and using local products readily available in the market.

“All the students have cooked very imaginative and delicious food,” said Emma Razanaparany the school principal. “As young people, they are in a position to influence their parents and change the way that future generations eat.”

Drought and malnutrition

Southern Madagascar is home to some of the country’s poorest communities in a region which is experiencing the destructive impact of climate change, including recurrent drought.

As their families struggle to grow enough nutritious food, almost half a million children under the age of five are suffering from acute malnutrition, according to the UN-backed integrated food security phase (IPC) classification.

UN agencies and partners have responded with humanitarian relief aid, but are also looking beyond the cycle of immediate crises at how to ensure the longer-term sustainable development of communities.

Joint approach to tackling challenges

Competitions like Tsikonina are one small part of that effort, which is bringing together multiple UN agencies in what the UN is calling convergence zones to develop and deliver activities.

These activities draw on the expertise of individual agencies to look at the underlying vulnerabilities facing communities and the best way to address them.

Beabo Primary School is a microcosm of that collaborative approach. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) have both worked with local women-led farming cooperatives to support the production of food which is used by the World Food Programme (WFP) as part of its home-grown food school feeding initiative.

Providing a nutritious meal to children at school not only improves their health and encourages them to stay in school, it also boosts the local economy by providing a market for the produce of local farmers.

Better access to clean water and sanitation

The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has helped to develop garden wells to provide more consistent access to water for the school as well as building a sanitation block and providing training to teachers and pupils on sanitation issues and resilience to climate change. It has also provided washing kits and pupil education packs.

“The lack of rain in this region brings many problems and worsens the living situation for people here,” said UNICEF’s Melanie Zafindrakemba, a nutrition specialist. “Providing access to clean water contributes to better hygiene and is safer for cooking and drinking and helps communities get through humanitarian crises.”

In addition to providing hot meals to vulnerable children, WFP has also trained parents and teachers to manage the school-feeding programme.

Foundations for long-term development

Meanwhile, the UN’s International Labour Organization (ILO) has significantly improved the school’s physical infrastructure by supporting the building of two classrooms, a school kitchen as well as providing desks and tables for teachers and pupils. As part of the process, it trained and employed local workers to carry out the construction project, further boosting the local economy.

“The synergy created by UN agencies working together in this school has been powerful," said WFP's Fidèle Andrianantenaina, who is based in Ambovombe. "There is a convergence of problems in this region, including food insecurity, poverty, lack of access to health and social services and few job opportunities, so a project like this can support long-term stability and development," he added.

Finding the synergy or complementarity between UN agencies is an important first step, the benefits of which are evident in this one UN-supported school. It’s now hoped that additional funding can be found to expand the approach not just to other schools across the region, but to other communities in need.

SDG 2: END FOOD INSECURITY

- End hunger and malnutrition and ensure access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food year-round for all

- Double small-scale food producers’ agricultural productivity and income

- Ensure sustainable food production systems and implement agricultural practices that increase productivity/production and strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change and disasters

- Correct and prevent trade restrictions in world agricultural markets

Globally, one in three people struggles with moderate to severe food insecurity.