Breadcrumb

Preserving, and enabling, the history of multilateralism: new online platform gives unprecedented access to UN Geneva archives

The United Nations Archives in Geneva have launched a new online platform that allows unlimited access to the institutional memory of the United Nations for everyone – from researchers and diplomats to UN staff and students.

Using state-of-the-art technology, the new service provides free digital access to a catalogue of collections that includes the League of Nations archives from 1920 to 1946, archives on international laws to protect refugees and minorities, the history of multilateralism, and international peace movements dating back to the late 19th century.

By giving access to everyone who is interested, “we are reinjecting the history of multilateralism into… research, thought leadership, academic and think-tanks,” says Francesco Pisano, Director of the United Nations Library and Archives in Geneva

For UN Geneva’s Director-General, Tatiana Valovaya, these archives are particularly valuable for today’s research on multilateralism. “In order to find answers and solutions to current challenges, it is important to learn from the past,” she says.

Some 150 people normally travel to Geneva each year to visit and research the archives in person. But since the launch of the digital platform in December, more than 8,600 individuals have already accessed the information online.

New chapter

For Christiane Sibille, a lecturer in digital history at the University of Basel, the digitization of historical documents, such as the UN Geneva Archives project, is “just the beginning”.

Speaking at a recent event organized by the UN Geneva Library and Archives, she explained that digitization enables librarians to use metadata to add layers of information in databases, such as indexing persons and locations, providing for better insight into documents and structured search possibilities.

“With research programmes increasingly using artificial intelligence to process data and reference documents, digitization is destined to open new horizons,” says Blandine Blukacz-Louisfert, Chief of the Institutional Memory Section at the United Nations Library and Archives in Geneva.

Browsing through the League of Nations archival material she could now find online, Dr. Stefanie Massink, a lecturer on the history of international relations at Utrecht University, recently tweeted: “A historian’s happiness = historical treasures...So immensely grateful for the digitization efforts,” she added, tagging UNOG and UN Libraries.

A historian’s happiness = finding historical treasures. Currently browsing interesting archive material from the League of Nations @UNOGLibrary. So immensely grateful for the digitization efforts @UNOGLibrary @UNLibrary 🙏💙

— Dr. Stefanie F. M. Massink (@StefanieMassink) February 21, 2022

Haakon Ikonomou, a teaching associate professor at the University of Copenhagen, agrees. He described the project as “an immeasurable service to history, historians (and other scholars) and the future understanding of internationalism and multilateralism.”

For one researcher from Brazil, the digitization of the League of Nations archives is a model to be followed, “as it really opens and democratizes the access to such a relevant source of information. I am sure that it will soon have an important effect in the research in this area.”

While the UN archives are now available online, Ms. Blukacz-Louisfert assures researchers that archivists remain available to anyone needing in-person assistance. Researchers can chat with them instantly through a virtual reading room, set up an online meeting, or access presentations and training opportunities.

Hidden gems

When asked about any hidden treasures uncovered during the project, Ms. Blukacz-Louisfert recalls how a customs document was found describing how the League of Nations was trying to standardize customs and trade.

“A list of goods including dried bananas was part of the correspondence destined to regulate customs and classify goods shipped back and forth. To everyone’s surprise, a sample received from the company - actual dried bananas from the 1920s - was uncovered in the file,” she recounts.

For Ms. Blukacz-Louisfert, this shows that the League of Nations was already addressing concrete and technical issues on international cooperation, which paved the way for the work the UN does today. And, in case you were wondering, true to the spirit of the digitization process, the dried bananas were also scanned and added to the online archive.

Another important aspect of the collection that was only recently discovered relates to refugee issues, including identification documents from the asylum seekers themselves and information about their experiences. This information is critical for providing a personal context to how policies were shaped at the time.

Also uncovered were many petitions, from individuals and groups who were writing to the League of Nations to promote their causes.

Colin Wells, Information Management Officer at the United Nations Office in Geneva, says that this showed that the League of Nations had provided a new forum for civil society organizations to address various issues, and that this helped establish the international NGO world that exists today.

Digitizing the collection, a mammoth undertaking

The new online archives platform is an important part of the LONTAD project (Total Digital Access to the League of Nations Archives Project).

Beginning in 2017, it has involved the digitization of 15 million pages – the equivalent of three linear kilometers – of primary sources, which are mostly in the form of written correspondence, as well as some publications and official documents.

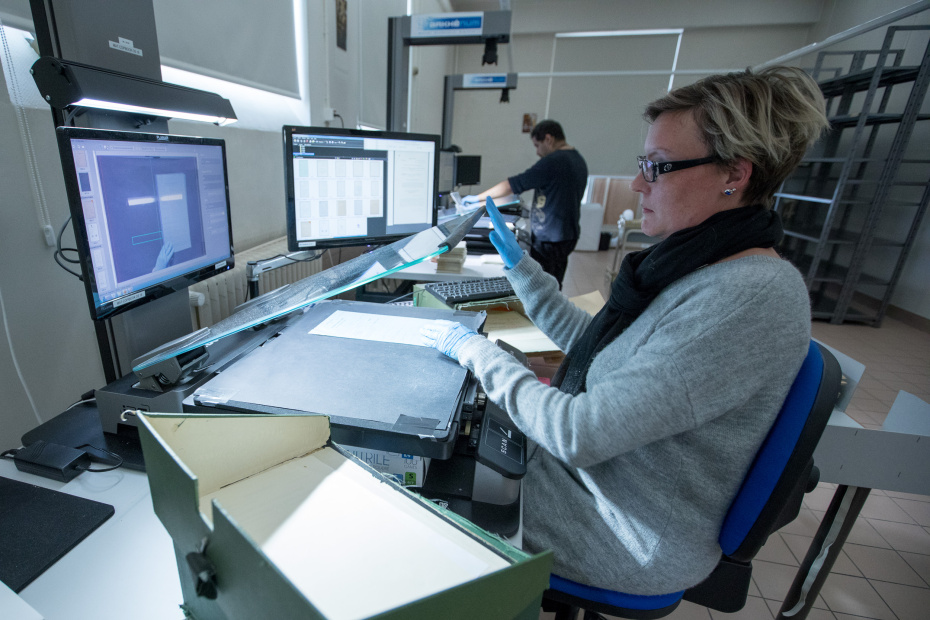

While close to 90 per cent of the collection has now been digitized, the process will continue for a good part of this year, too. It keeps busy a team of close to 30 people who were trained by a Library specialist in conservation and preservation.

Colin Wells, Head of the LONTAD digitization project, says the project is labor-intensive, with every single page of the 15 million documents needing to be scanned individually. Before this can happen, Mr. Wells explains that there is a pre-digitization process, which involves preparing the materials physically for scanning.

Finally, there is the post-digitization phase, during which the images are checked for quality and descriptions are added, including titles, dates and other critical information providing context. "This is absolutely key to ensure that the images are searchable and usable by researchers," says Mr. Wells.

Throughout the process, workers also take time and care to perform additional physical preservation works, such as minor repairs, to prolong the lives of the original materials for as long as possible, or removing bindings. Until recently, five to six people worked on preparation on a full-time basis, every day for four years.

A specialized team is also dedicated to working on geographical maps alone, which total 35,000 in the collection.